A DECADE OF DEVELOPMENT AT THE PORT OF MONROE FOR PAUL C. LAMARRE III

Anything you have read about the Port of Monroe, Michigan in the last decade would not be possible without the leadership of Paul C. LaMarre III.

Paul is celebrating 10 years at the helm of the Port this season, and the rebirth of Monroe as a seaport is just one of many reclamation projects that he has conducted over the years.

His most notable work is saving the 1911-built freighter Col. James M. Schoonmaker, which is now the centerpiece at the growing National Museum of the Great Lakes. Paul became director of the scrapyard-bound museum ship in 2007 when it was known as the Willis B. Boyer and guided the ship through a massive restoration.

The ship was moved from its old berth in Toledo to its present dock in 2011. The process included a return to the ship’s original name and livery of the Shenango Furnace Company.

Completing such a monumental task would leave some people content, but not Paul. The retired Great Lakes Towing Company tug Ohio was restored in 2019 and dedicated to the museum in a joint ceremony with the new tug Ohio, christened by Paul’s wife, Julie.

When the 100-plus-year-old steamer St. Marys Challenger was converted to a barge at Sturgeon Bay in 2013, the pilothouse was removed and transported to Toledo on the deck of the thousand-footer Paul R. Tregurtha – an unconventional move orchestrated by Paul. The pilothouse was offloaded at Midwest Terminals and remained there until December 2021 when the final move to the museum was made. It was fitting then, that the St. Marys Challenger was also in Toledo that day, holding up a piece of her own heritage.

The projects don’t stop there- the pilothouse of the old tug Wm. A. Whitney is in Paul’s backyard, being restored. You can see the spotlight he installed shine all the way to Detroit River Light after dark.

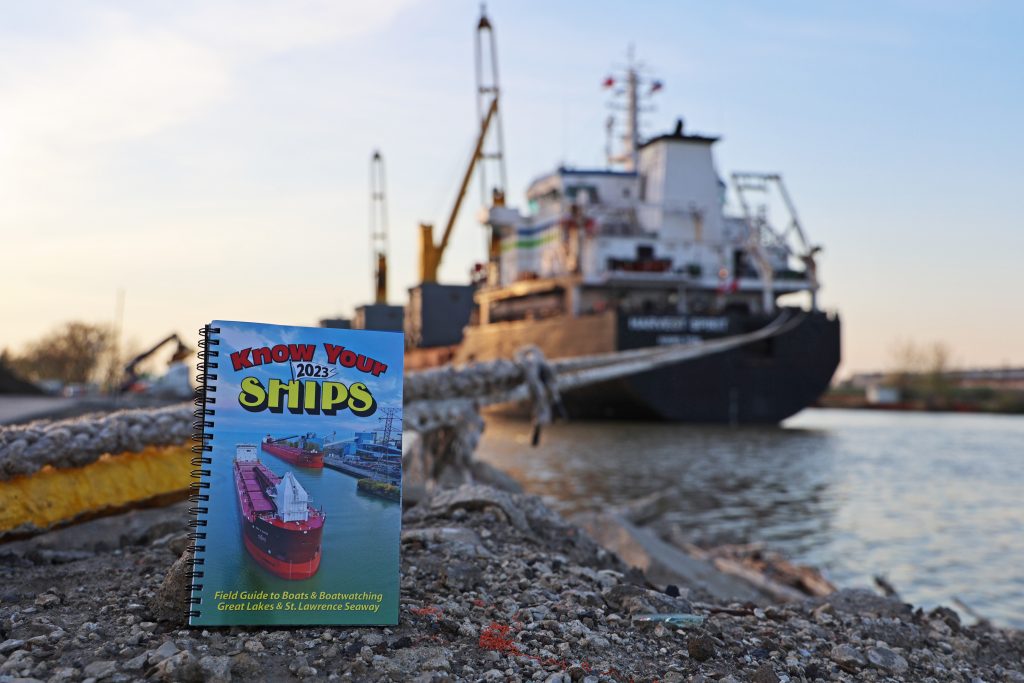

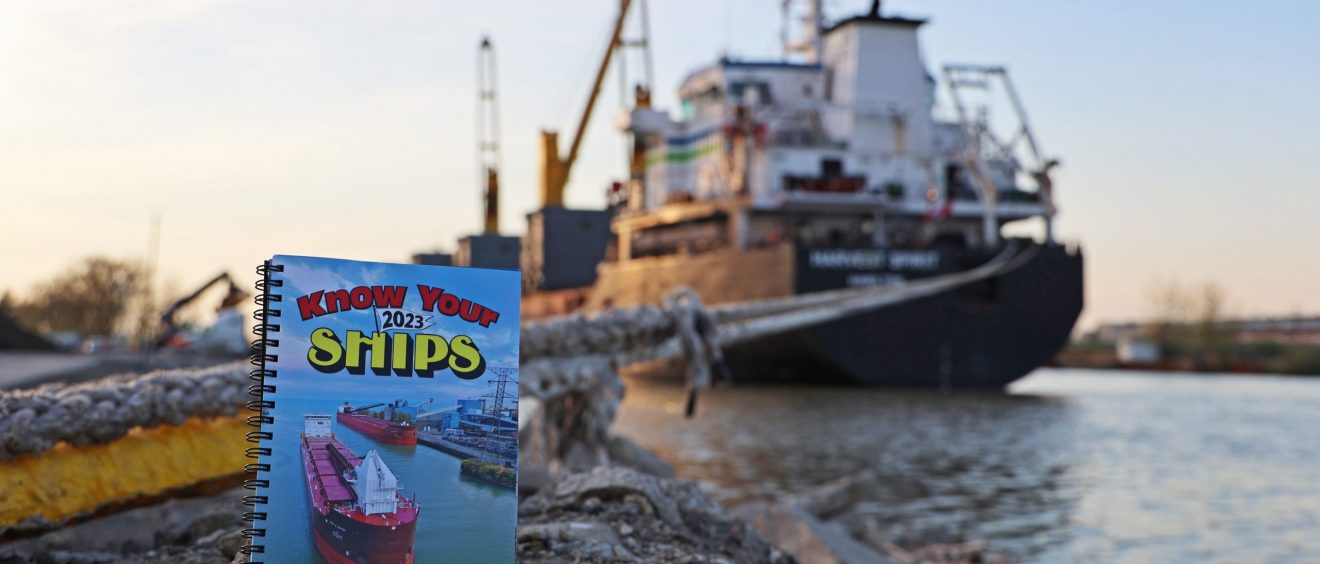

There’s still room in his yard for more. Close friend Roger LeLievre, publisher of the book Know Your Ships, theorizes that with Paul’s unrelenting drive, he could get the Queen Mary in his backyard if he said he would.

Once complete, these restoration projects serve as relics to the past of the Great Lakes, honoring the heritage and history of the inland seas. In the present day, they serve an additional purpose: Making people believe.

Paul sketched the original layout for the National Museum of the Great Lakes on a napkin, when the future of the Schoonmaker, then-Boyer was in doubt. Restoring the ship and establishing it as the anchor for a larger museum development made people believers.

It was Paul’s passion for restoring the heritage of the Great Lakes that put him on the radar of other ports. He had given a number of presentations about Great Lakes history and the Schoonmaker at industry events, and the Monroe Port Commission took notice.

Paul took a rusting museum ship and established it as the unquestionable anchor of a larger development on Toledo’s waterfront, using his knowledge and passion of the industry to sell people on his vision.

The Port of Monroe, established in 1932, had been dormant for decades. Past eras of leadership left behind legacies of feasibility studies and advertising promotions that led to no cargo. The fit was obvious. When the commission decided to rebuild the port, they quickly determined that a director was needed to shape Monroe’s future, and Paul became the obvious candidate.

He became Port Director in 2012, at a port with no activity, outdated infrastructure, and a waterfront that had no indication of ever being used for port operations. It was a daunting task, but Paul set to work on identifying cargo in Monroe’s backyard that could be moved through the Port. That focus led to a partnership with DTE to manage synthetic gypsum produced from the Monroe Power Plant in 2014, which remains a foundational cargo at the Port.

From there, Paul combined his passion for the Great Lakes shipping industry with the need for speed he acquired first in his days flying F/A-18s in the Navy and later racing hydroplanes, and rapidly awakened the once-sleepy Port.

Monroe has notched six Pacesetter awards in Paul’s tenure as director, consistently celebrating new cargo evolutions and welcoming new ships. The Port has focused on niche cargo moves unique from traditional cargoes carried on the lakes, and welcomed several ships on their maiden trip into the Great Lakes/St. Lawrence Seaway System.

In addition to earning an unlimited deck officer’s license, Paul is now working to attain a Masters of Towing license, which will give him more opportunities on the water. He’s also becoming an accomplished marine artist- just like his father, Paul C. LaMarre Sr.

Development is not limited to ships and ports, either. Paul has always taken a relationships-first approach to everything and is actively helping chart the course for the next generation of maritime leadership, whether that’s on the docks or on the boats. He’ll always lend an ear to anyone in the maritime industry looking for support.

Paul has preserved each and every activity the Port has undertaken in photos. Documenting everything shows the community how the Port has grown and highlights the Monroe County residents that work at the Port.

However, one of the most inspirational photos taken at the Port since Paul’s arrival doesn’t include a ship or a cargo. It’s a day-one snapshot showing an inactive port with overgrown trees as the only tenant. It helps remind everyone of where we came from.

Now, where can we go? The future is unwritten, but when it is, Paul C. LaMarre will be the one holding the pen.

Written by Samuel Hankinson

This article originally appeared in Seaway Review